Escape from the Planet of the Apes

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

| Escape from the Planet of the Apes | |

|---|---|

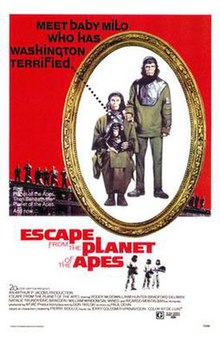

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Don Taylor |

| Written by | Paul Dehn |

| Based on | Characters by Pierre Boulle |

| Produced by | Arthur P. Jacobs |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph F. Biroc |

| Edited by | Marion Rothman |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production company | APJAC Productions |

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[2] |

| Box office | $12.3 million[3] |

Escape from the Planet of the Apes is a 1971 American science fiction film directed by Don Taylor and written by Paul Dehn. The film is the sequel to Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) and the third installment in the original Planet of the Apes film series. It stars Roddy McDowall, Kim Hunter, Bradford Dillman, Natalie Trundy, Eric Braeden, Sal Mineo, and Ricardo Montalbán.[4] In the film, Cornelius (McDowall) and Zira (Hunter) flee back through time to 20th-century Los Angeles, where they face fear and persecution.

Escape from the Planet of the Apes was released in the United States on May 26, 1971, by 20th Century-Fox.[1] The film received a mainly positive response from critics and is generally considered the best sequel of the original Apes series. Escape was followed by Conquest of the Planet of the Apes in 1972.

Plot

[edit]Prior to Earth's destruction,[a] the chimpanzees Cornelius, Zira and Dr. Milo salvage and repair Taylor's spaceship and escape the planet. The shock wave of Earth's destruction sends the ship through a time warp that brings the apes to 1973 Earth. Most specifically, the Pacific coast of the United States.

The apes are transported to the Los Angeles Zoo, under the observation of two friendly scientists, Dr. Stephanie Branton and Dr. Lewis Dixon. During their stay there, Dr. Milo is killed by a zoo gorilla.

A Presidential Commission is formed to investigate the return of Taylor's spaceship and its inhabitants. During their interrogation, Cornelius and Zira deny knowing Taylor. They reveal, however, that they came from the future and escaped Earth when a war broke out. They are welcomed as guests of the government. The apes secretly explain to Stephanie and Lewis how humans are treated in the future, and tell them about Earth's destruction. The scientists are shocked but still sympathetic, and advise the couple to keep this information secret until they can gauge the potential reaction of their hosts.

Lavished with gifts and media attention, the apes become celebrities. They come to the attention of the President's Science Advisor Dr. Otto Hasslein, who discovers Zira is pregnant. Fearing for the future of the human race, Hasslein insists that he simply wants to know how apes became dominant over men. Cornelius reveals that the human race will cause its own downfall and that Earth's destruction is caused by a weapon made by humans. Zira explains that the gorillas started the war, but the chimpanzees had nothing to do with it. Hasslein suspects that the apes are not telling the whole truth.

During the original hearing, Zira accidentally reveals that she used to dissect humans. Hasslein orders Lewis to administer a truth serum to her while Cornelius is confined elsewhere. As a result of the serum, Hasslein learns details about Zira's experimentation on humans along with her knowledge of Taylor.

Zira joins Cornelius in confinement while Hasslein takes his findings to the President, who reluctantly abides by the council's ruling to have her pregnancy be terminated and that both apes be sterilized. In their chambers, Zira and Cornelius fear for their lives. When an orderly arrives to offer the apes food, his jokes about their future child make Cornelius lose his temper. He knocks the orderly to the floor, before escaping with Zira. They assume the orderly is merely knocked out, but he is actually dead. Hasslein uses the tragedy in support of his claim that the apes are a threat. He calls for their execution, but is ordered by the President to bring them in alive, unwilling to endorse capital punishment until due process has been served.

Branton and Dixon help the apes escape, taking them to a circus run by Señor Armando, where an ape named Heloise has just given birth. Zira gives birth to a son and names him Milo, in honor of their deceased friend. Knowing that Zira's labor was imminent, Hasslein orders a search of all circuses and zoos, and Armando insists the apes leave for their safety. Lewis arranges for the apes to hide out in the Los Angeles harbor's shipyard for a while. He gives Cornelius a pistol as the couple does not want to be taken alive.

Tracking the apes to the shipping yard, Hasslein mortally wounds Zira and kills the infant she is holding. Cornelius shoots down Hasslein, and then dies at the hands of a sniper. Zira tosses the dead baby over the side and crawls to die with her husband, witnessed by a grieving Lewis and Stephanie.

It is revealed that Zira switched babies with Heloise before leaving the circus. Armando is aware of this and prepares to leave for Florida. Baby Milo then begins to talk.

Cast

[edit]- Roddy McDowall as Dr. Cornelius

- Kim Hunter as Dr. Zira

- Bradford Dillman as Dr. Lewis Dixon

- Natalie Trundy as Dr. Stephanie Branton

- Eric Braeden as Dr. Otto Hasslein

- William Windom as President of the United States

- Sal Mineo as Dr. Milo

- Albert Salmi as E-1

- Jason Evers as E-2

- John Randolph as the chairman

- Harry Lauter as General Winthrop

- M. Emmet Walsh as Aide

- Roy Glenn as the Lawyer

- Peter Forster as the Cardinal

- Bill Bonds as Himself

- James Bacon as General Faulkner

- Ricardo Montalbán as Armando

- George P. Wilbur as boxer Uncredited

In this film, actor Roddy McDowall returns to the character of Cornelius which he played in the first film but not in the second. A new ape character of Dr. Milo is introduced played by actor Sal Mineo. Charlton Heston, star of the first film and supporting actor in the second, appears in this third installment only in two brief flashback sequences.

Production

[edit]Despite Beneath the Planet of the Apes ending in a way that seemed to prevent the series from continuing, 20th Century-Fox still wanted a sequel. Roddy McDowall, in the franchise documentary Behind the Planet of the Apes, stated that Arthur P. Jacobs sent Beneath screenwriter Paul Dehn a telegram concerning the sequel that read "Apes exist, Sequel required." and Dehn decided to create an out from the destructive ending of Beneath by having Cornelius and Zira going back in time with a Leonardo da Vinci–like ape after fixing Taylor's spaceship before the Earth was destroyed. Dehn also consulted Pierre Boulle, writer of the Planet of the Apes novel, to imbue his script with similar satirical elements. The screenplay, originally titled Secret of the Planet of the Apes, accommodated the smaller budget by having fewer people in ape make-up, and attracted director Don Taylor by its humor and focus on the chimpanzee couple.

Dehn also added to the latter part of the film regarding the chase for Cornelius, Zira and their son references to racial conflicts and a few religious overtones to the story of Jesus – a line of dialogue even has the President comparing the plan to kill an unborn child to the Massacre of the Innocents.[5][6] While Kim Hunter had to be convinced by the studio to make Beneath, she liked the script for Escape from the Planet of the Apes and accepted the job, though Hunter also stated that "I was very glad I was killed off" and Zira was not required anymore after that film. Hunter stated that despite the friendly atmosphere on the set, she and Roddy McDowall felt a sense of isolation for being the only people dressed as chimpanzees.[citation needed] Production was rushed due to the low budget, being filmed in only six weeks,[7] from November 30, 1970 to January 19, 1971.[8]

Music

[edit]Personnel

[edit]- Cappy Lewis – trumpet[9]

- Phil Teele – trombone[9]

- Vincent DeRosa, John Cave – French horn[9]

- Russ Cheever, Abe Most, Dominic Fera – clarinet[9]

- Don Christlieb – bassoon[9]

- Artie Kane – piano[9]

- Bob Bain, Al Hendrickson – guitar[9]

- Carol Kaye – electric bass[9]

- Larry Bunker, Shelly Manne – percussion[9]

Reception

[edit]According to Variety, the film earned $5,560,000 in rentals at the North American box office.[10]

The film holds a 77% score on Rotten Tomatoes based on 30 reviews. The critical consensus reads: "One of the better Planet of the Apes sequels, Escape is more character-driven than the previous films, and more touching as a result."[11]

Roger Greenspun of The New York Times was positive, finding the premise "quite beautiful" with the theme of human guilt "richly ambivalent, because the monsters are scarcely monstrous and the guilt is a function of unassailable strategic intelligence."[12] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three stars out of four and wrote, "Comparatively, it is much better than the second, which was awful, but not as good as the first, which was quite good."[13] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety called it "an excellent film. Far better than last year's followup and almost as good as the original 'Planet of the Apes.'"[14] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "works largely because Miss Hunter and McDowall, working under Don Taylor's deft direction, are such gifted actors and because John Chambers' chimpanzee makeup is so convincing, as it was in the other pictures."[15] David Pirie of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "Infuriatingly, Escape from the Planet of the Apes continues the downward trend of a science-fiction series that started out with much ingenuity and promise ... the film is painfully sentimental in its attitude to the chimps, with Kim Hunter and Roddy McDowall overplaying and vulgarising their former roles to the point where it's hard to feel much concern about their final destruction."[16]

Spin-off media

[edit]A comic book miniseries, a crossover with Star Trek serving to bridge the events of the second and third films and titled Star Trek/Planet of the Apes: The Primate Directive, was published from December 2014 to April 2015.

Notes

[edit]- ^ As depicted in Beneath the Planet of the Apes.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ Solomon, Aubrey. Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1. p256

- ^ "Escape from the Planet of the Apes, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Those Damned Dirty Apes!". www.mediacircus.net. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ^ "The Secret Behind Escape", Escape from the Planet of the Apes Blu-ray

- ^ Hofstede, David. Planet of the Apes: An Unofficial Companion

- ^ Chimp Life, by Tom Weaver & Michael Brunas – Starlog (November 1990)

- ^ Planet of the apes : 40-year evolution / written by Lee Pfeiffer & Dave Worrall. Published by Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, c2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Escape from the Planet of the Apes". Library of Congress.

- ^ "All-time Film Rental Champs", Variety, 7 January 1976 p 46

- ^ Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971). Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- ^ Greenspun, Roger (May 29, 1971). "'Escape From the Planet of the Apes' Proves Entertaining". The New York Times. 10.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (May 24, 1971). "Planet of Apes..." Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 14.

- ^ Murphy, Arthur D. (May 26, 1971). "Film Reviews: Escape From The Planet Of The Apes". Variety. 23.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (May 27, 1971). "Third 'Ape' Film Opens Engagement". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 12.

- ^ Pirie, David (August 1971). "Escape From the Planet of the Apes". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 38 (451): 164.

External links

[edit]- 1971 films

- 1970s dystopian films

- 20th Century Fox films

- American science fiction films

- American science fiction adventure films

- American sequel films

- 1970s films about time travel

- Films directed by Don Taylor

- Films scored by Jerry Goldsmith

- Films set in 1973

- Films set in the future

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Michigan

- Films with screenplays by Paul Dehn

- Planet of the Apes films

- Sterilization in fiction

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- 1971 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction films